I think one thing everyone can agree on when it comes to the work of Guillermo del Toro is that his movies speak to a universality that lies in the subconscious; our survivalist need for stories to be told, or more simply for entertainment lest we go crazy. Everyone learns this at a very young age when they hear their first fairy tale, and del Toro almost always manages to encapsulate the childlike fun and imagination of Old World fantasy and inject it with New World grit and reality. Most people first experience del Toro via Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), a fable of a young girl living in fascist Spain who discovers a fantastical realm. All of his films are premised like fables, and this all started with a bit of 90s body horror called Cronos (1993).

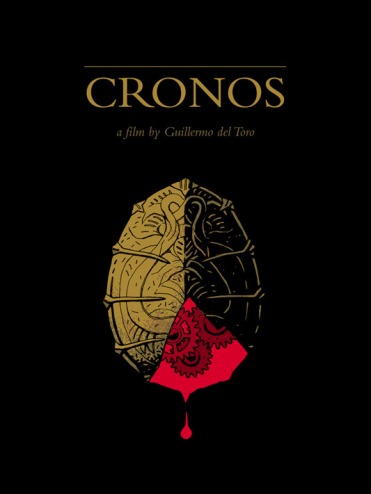

Cronos is a film that, without its Criterion Collection release, could have been forgotten as a strange but effective 90s horror film. It certainly is not as good as his later work, but it holds up well and reflects the various motifs and visual elements that his more popular films thrive on. The movie follows an old antique shop owner, Jesús Gris (Federico Luppi), who finds a gold device in one of the statues in his shop while spending time with his granddaughter (Tamara Shanath). When the gold automaton is winded it unfurls spider-like limbs that grip his hand and sting him. Jesús’ hand gets gored, but he realizes that he looks and feels much younger. A rich business man, Dieter de la Guardia (Claudio Brook), has been tirelessly looking for that exact device as it contains the secret to immortality, but now Jesus is determined to keep it for himself.

Bam. There’s your premise. It’s another variation on the familiar horror idea of what happens when god-like power falls into the hands of a regular schmuck. It’s not very original, but del Toro is not exactly the kind of filmmaker who worries about that sort of thing. He set out to tell a fountain of youth story and tells it well. We primarily follow Jesús as he discovers the power of the automaton while occasionally cutting back to de la Guardia and his henchman nephew (a youthful and charismatic Ron Perlman) scheming to get it back from the shop owner. Jesús’ granddaughter plays into the story more as the film goes on – par for the course with del Toro’s childhood innocence theming – but for the most part everything is kept straightforward and no supplementary sub-plots are introduced that don’t have to do with the literal plot device. This works to the film’s benefit as this allows us to spend more time with Jesús as he grows increasingly dependent on the automaton’s injections. The discomfort we develop from watching him grow increasingly ravenous yet secretive with every repeated dose is where the real “horror” of the film comes from, and these scenes are always perfectly shot and paced to deliver the right combination of seriousness and disgust. Jesús even develops a vampiric obsession with consuming blood, to the extent of licking it off of a men’s bathroom floor at a party, and this along with the automaton violently stabbing its user injects an otherwise patient and somber film with some 90s over-the-top gross out gore.

Seeing Jesús’ concerned granddaughter helplessly watch her increasingly manic grandfather spiral, we realize that Cronos is more than just a horror tale of depravity and obsession. It is just as much a drama with a drug-addiction metaphor, about the effects drug use has on the individual and the family, which is unfortunately as much a negative as it is a positive in this film. The difference in tone between Jesús literally transforming into a sort of vampire and the scenes that build on the relationship with his granddaughter Aurora – even using her in a Spielbergian heist-adventure in the latter half of the film to prevent de la Guardia and his nephew Angel from acquiring the automaton – feels drastically inconsistent. The few long shots of Aurora looking at her grandfather dejectedly pull at heartstrings and certainly add much-needed dramatic weight to Jesús’ arc, but the absolute insistence in her maintaining a presence in the story feels forced. I suppose by nature of her being a young child she can’t add much intellectually or otherwise to a story where the “druggie” shoots up with immortality in private and his rivals resort to violence and intimidation to get it, but I can’t help but feel she could have been utilized more to legitimize her presence in the plot outside of her eventual importance in the climax. Perhaps a scene or two with the comic relief Angel could have sufficed, I don’t know. Ultimately I can forgive this due to the fact that this is a directorial debut, and del Toro had yet to perfect his dedication to straightforward genre like in Crimson Peak (2015), or the balance between fantastical elements and grounded-in-reality elements like in Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), which makes the young girl the protagonist.

Despite a lot of repetition in the writing and some tonally inconsistent elements, this is a solid first time effort that is full of as much gore and depravity as it is with worthwhile themes and motifs. Del Toro is, for good reason, one of the best, if not the best, genre filmmakers working today and it all started with Cronos. Even though his roots are in horror, a genre that many people react standoffishly to, he cares first and foremost about telling stories and embracing the fantastical elements of storytelling. And in 1993 nothing is more fantastical, more entertaining, or more bizarre than a film in which an alchemist builds an immortality machine using an insect because he realized that Jesus Christ walked on water like a mosquito.–@mageeethan